-

-

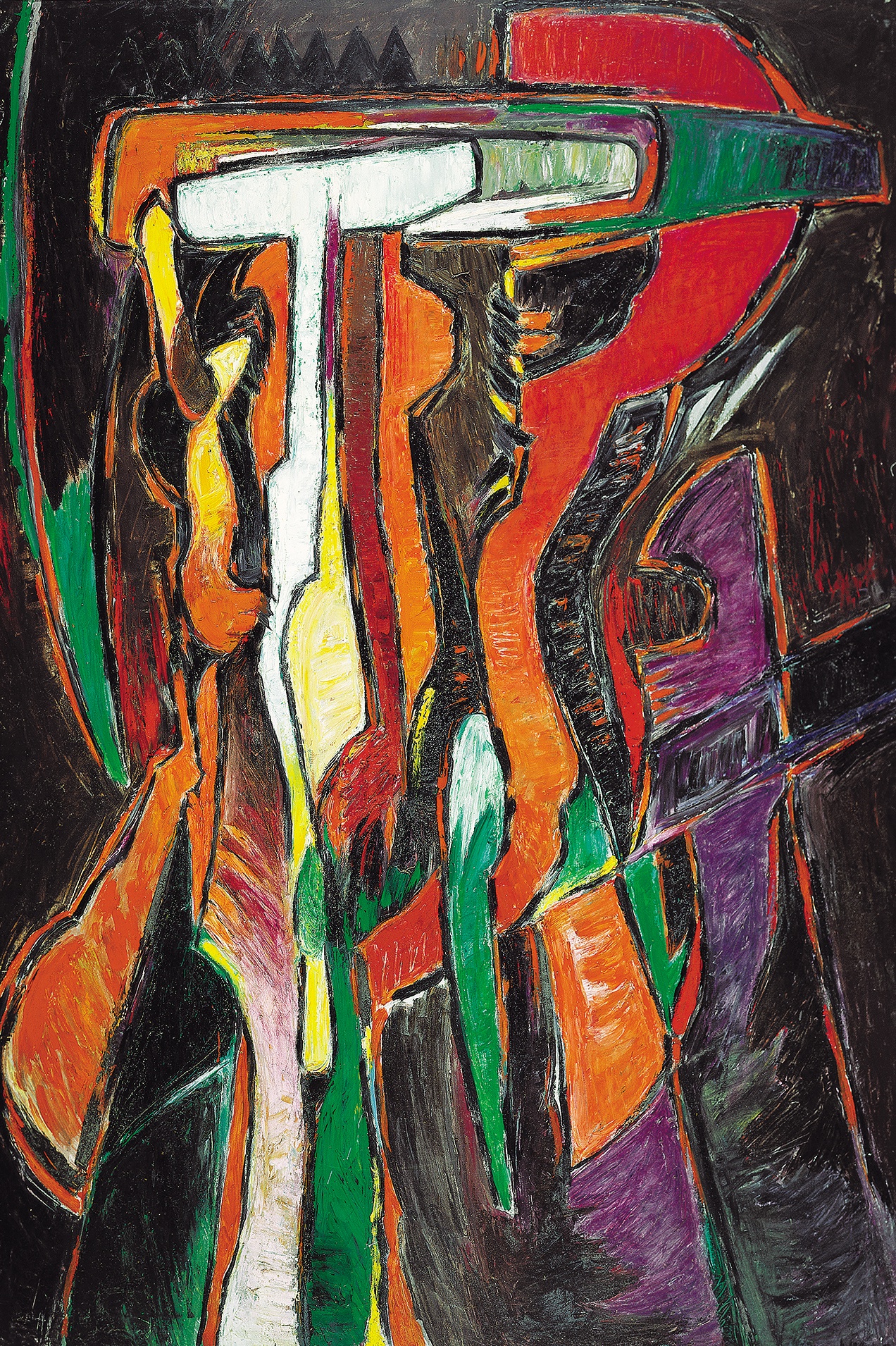

Ancestral, 1976, Oil on canvas,195 x 133cm

Click to listen

At first sight, Ancestral looks like an informal cascading of colors on a dark background. However, the silhouette of a white ghostly figure finds its way to the forefront of the composition. It is only then that the viewer recognizes the stylization of the horizontal white head echoing a larger one in orange and green. The latter interlocks with a suspended reddish element stemming from the bottom of this monumental composition. The title of the painting, Ancestral is also a clue that metaphorically asks the viewer to enter the world of tradition, the realm of the deceased from which we descend. This is perhaps the most challenging painting in the exhibition and that difficulty to penetrate the mysterious past also makes it one of the most attractive.

Vigas once described that even his most abstract works have a “ghost”of figuration. He considered them within the category of Magical Realism with a dose of Surrealism. Magical Realism, as pointed out by Cuban writer Alejo Carpentier, is the most relevant characteristics of Latin American art and literature. And this particular Surrealism Vigas mentioned doesn't share the same values with the movement in Europe. It is Latin American Surrealism.

Vigas believed that, the awareness of an artist's own values is the fundamental spiritual element that can rescue the sense of identity from being lost. There are levels of consciousness in which the past and the present can be fused. That is why he considered that an archaic image, as a formal value, is richer in content and much more "valid" than what could be considered a mere modern form.

-

Composición en Gris (Composition in Grey), 1954, Oil on cardboard, 58 x 43cm

In an interview in the late 70s, Vigas declared that his “painting has never been abstract. It has been the reduction of the human figure to an abstract sign.” Reduction is a long, laborious process. It takes time to crystalize elements into their essentials in order to produce a more intense and perhaps surprising result.

Vigas studied the human form in two radically different ways: On one hand, his study of medicine must have given him a strong sense of the human body. On the other hand, as an artist, he needed to create “figures” out of those bodies with his own expressions.

Vigas drew inspiration from 20th century masters, most notably Picasso and Uruguayan Constructivist Joaquin Torres García, the founder of the Circle and Square movement in the late 1920s. While Picasso had famously taken fundamental elements of African Art to reduce his own figures into strong graphic shapes, Torres-García’s revolutionary compartmentalization isolates formal elements, signs and symbols in a style he called Constructive Universalism.

In the work Composition in Grey, Vigas invites us to explore his signs. Are those leaves as hinted by the green shades on the left? Or are there two figures emerging from the background with a stylized hand at the bottom? Does the oval head shape remind you of African mask?

-

Untitled, 1962, Oil on canvas, 92 x 73cm

While in Paris, Vigas obsessively worked on a series of abstract expressionist paintings, giving free rein to the kind of plastic automatism that had inspired the New York school of the 1950s. It was what Robert Motherwell described as “a plastic weapon with which to invent new forms” characterized by improvisation and dynamic gestures.

Most of the paintings in this series were in effect an exercise of liberty. Turning 40 years old, Vigas found himself at a peak in his career, and was deliberately changing course. Having painted in a figurative and then in a constructivist manner for most of the 1950s, he first turned his attention to abstract and monochromatic landscapes like Fertile Stones, which is also shown in this exhibition.

Then in the early 60s, another new Vigas emerged. The artist suddenly expressed an urgent need to break loose and allow his vitality and his instincts to take over. Some critics have described these vigorous paintings as wild calligraphic essays, others have seen in them distressing pictograms.

To Vigas, these irrational free forms evoke one’s sensations, through which he or she finds a deeper understanding of things beyond rational thinking. As he put it, “when you drink a glass of water, do you understand water? The most you can say is that it satisfies you to drink it, but you cannot say that you understand it … Do you understand the scent of a flower? You smell it and feel it, it is part of the realm of sensations, but it has nothing to do with rationality-- that is [the meaning of] understanding.”

-

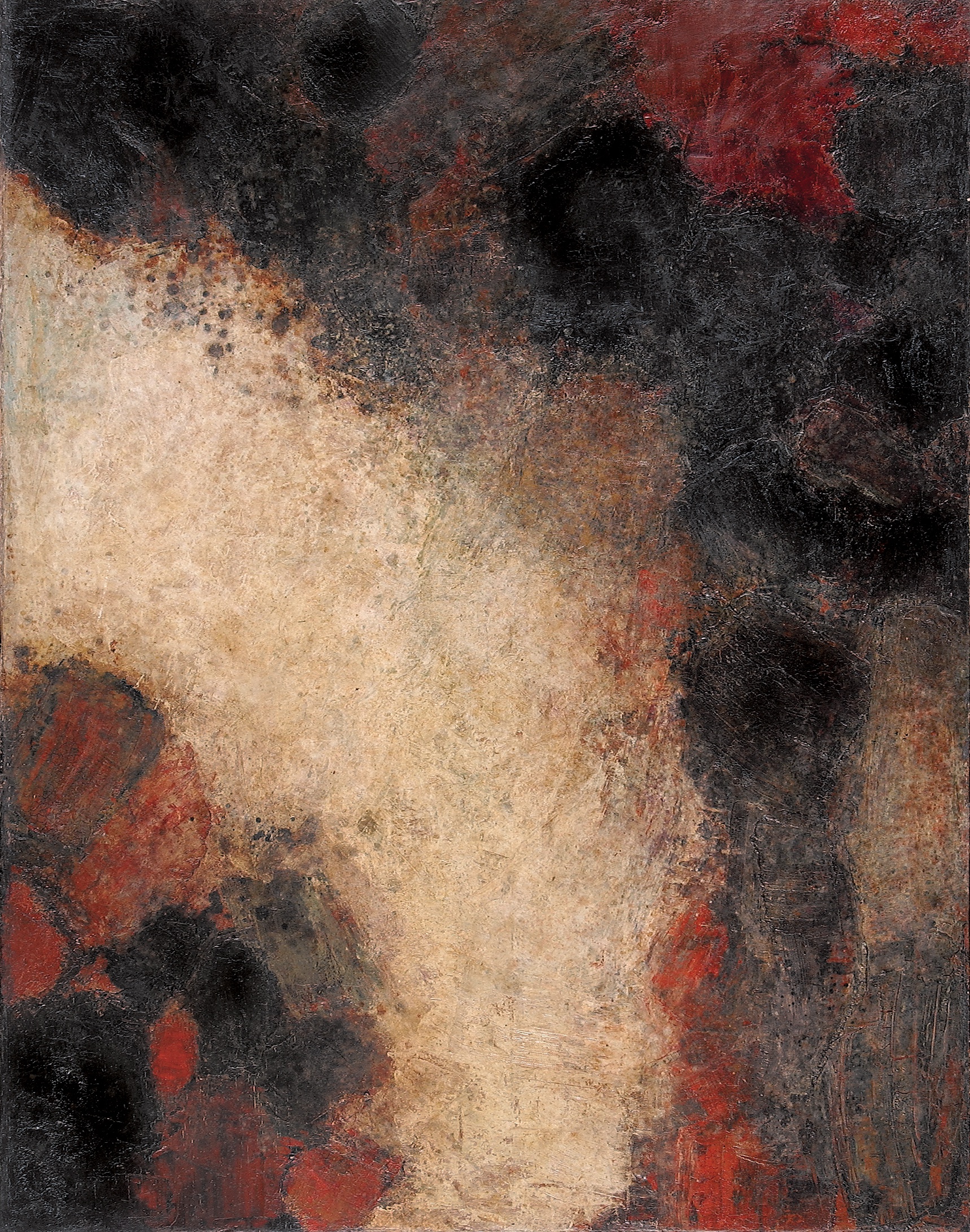

Piedras Fértiles I (Fertile Stones I ) , 1960, Oil on canvas, 146 x 113cm

At the end of the 1950s, Vigas briefly returned to his home country Venezuela from Paris. There, he encountered a new nationalist effervescence emerged after the overthrow of the military dictatorship. Vigas felt a duty as an artist to participate in the construction of a national art movement, to establish his Latin American identity with a universal modern language.

At that time, avant garde artists advocated an informal, non-representational approach to art, placing emphasis on spontaneity and gestural expressions. Vigas, together with his peers in Paris, such as Spanish Catalonian Antoni Tapies, Italian Alberto Burri and Mexican artists Rufino Tamayo and Francisco Toledo, these artists felt the same sense of urgency to signify the regenerative power of nature, of their mother lands, with an artistic vocabulary that is at once raw and deeply poetic.

This painting, Fertile Stones I, is a magnificent example of this Informalist period of Vigas. The hard, rocky, dark land is metaphorically fertilized by a river of light or water. What better tribute to the resurrection of the homeland is there than this life-giving force channeled through the paint?

-

Lúdica III (Playful III), 1970, Oil on canvas, 100.5 x 80cm

Picasso once said that “there is no abstract art. You must always start with something. Afterward you can remove all traces of reality.”

Paintings like Playful III could very well represent the process described by the great master, one of Vigas most important influences. To play is to joyfully interact with others. At first look, the image subtly suggests a child in the bottom left quadrant reaching out for his mother on the upper right. If we let the imagination play with the forms, we may also discover that the mother has green breasts and an open mouth as if talking to the other suggested figure, perhaps a male figure completing the family scene.

Any interpretation is of course speculative. Vigas's fundamental concern is to create a cohesive collection of forms and colors, a puzzle with independent pieces that will methodically fall into place to build a beautifully balanced composition.

-

Asmodé II (Asmodeus II), 1972, Oil on masonite, 100 x 70cm

Vigas approached abstraction very differently from his Venezuelan contemporaries in Paris. Jesús Soto, Alejandro Otero, and later Carlos Cruz Diez had a phenomenological approach to the construction of their art, meaning they were interested in the physical truths like how the movement of the viewer interact with the work, how colors interact with each other, and how they are perceived by the eyes.

For Vigas, this scientific approach to art was nonsensical. He strongly believed in the importance of the “what”, over the “how and the when”; art has to mean something, however figurative or abstract the work may appear to be. Commenting on the powerful meaning of an image, Vigas explained that “whatever a simple pictorial image ends up meaning is something absolutely unpredictable, since, to a large extent, it depends more on the experiences of the observer than on the intentions or desires of the painter.”

Paintings like Asmodé II can be interpreted in many ways. The name Asmodeus, in the Classical world, was originally given to a wild creature representing lust and sexual desire. Is it a centaur raping the white female figure on the right, much like the many representations of the God Zeus raping Princess Europa? Is it a tender embrace? Or is it simply a composition in elegant grey, white and yellow forms? As the artist said: "It will depend on what the viewer projects onto the image."

-

Ofrenda (Offering), 1977, Oil on canvas, 200 x 150cm

Popular Latin American spiritual practices and prayers are often directed to a number of divinities or spirits from indigenous, African and transcultural traditions, often associated with or assimilated by the post-colonial Christian saints. Offerings to gods and ancestors are also a common practice in rituals around the globe.

Vigas considered himself a mestizo, a Spanish term for culturally mixed man. And he manifested such identity in his paintings. Vigas’s native country, Venezuela, gave the artist the opportunity to connect with multiple subject matters related to ancient and modern belief systems based on a cast of many mythical and historic personages from various cultural influences.

In Offering, we perceive three or four stylized characters appearing from an indistinct background, holding fruits on a platter. Interestingly, these figures appear to be emerging from a luminous exterior as if entering a darker place of worship. Although the appearance of the worshipers seems static, movement is suggested by the strong diagonals and horizontal lines. The frontal character with round head and open arms seems to be in a state of ecstasy with open arms suggesting submission and adoration.

-

Ave y Personaje II (Bird and Character II), 1977, Oil on canvas, 150 x 200cm

“Bird and Character II” was painted in the same year as “Ofrenda”, which is also displayed in this exhibition. The two paintings could not be more different despite some shared formal aspects. A resourceful colorist, Vigas freely navigated a vast range of chromatic values which gave rise to an uncommon sense of volume. In effect, Vigas has remained faithful to the two-dimensionality of the canvas, on which he narrates with gestural lines and expressionistic colors.

Norwegian art critic, Karl Ringstrom, once wrote about this interesting trait of the artist’s approach to the canvas. He described how Vigas abandoned the classical perspective and his lines are configured in an imaginary space. As a result, the images become stronger and more imaginative, and the colors, treated with impetus, become more violent. Bird and Character II is a powerful example of this strategy.

-

Pareja de Curanderas (Pair of Healers) , 2010, Oil on canvas, 200 x 130cm

From the early 1990s, Vigas's figures became increasingly prominent, standing out from the background with strong black outline and sometimes additional aura-like contour of bright, contrasting colors; at the same time, these figures were also increasingly fragmented and deformed to the extent of comical; vibrant colors, spontaneous mark making and imaginative shapes of the body parts bring to mind the frankness and naivety in children's painting. To Vigas, revitalizing disappearing traditions requires the original creative impulse we all share in childhood.

Shifting his attention to contemporary life, Vigas expanded his subject matters to the ephemeral moments of the everyday. The stillness and mysterious air from previous periods gave way to dynamic and even playful compositions. His figures abandon the lonesome frontal posture and take on a new narrative power in their movements and interactions. However, the primordial energy that dominated his earlier works is not lost, it is hidden within the creatures, summoning their animal drive and instincts.

In Pair of Healers, two characters who practice traditional medicine or shamanism seem to be transported to the modern world from the past. Seemingly dressed in traditional costumes, they maintain their human form which is rare in the works from this period, but the execution is raw and child-like. In the world of science, is there still a place for spiritual healing and magic?

Audio Guide | Oswaldo Vigas:Return, Always Return

Past viewing_room